Strophoid

In geometry, a strophoid is a curve generated from a given curve C and points A (the fixed point) and O (the pole) as follows: Let L be a variable line passing through O and intersecting C at K. Now let P1 and P2 be the two points on L whose distance from K is the same as the distance from A to K. The locus of such points P1 and P2 is then the strophoid of C with respect to the pole O and fixed point A. Note that AP1 and AP2 are at right angles in this construction.

In the special case where C is a line, A lies on C, and O is not on C, then the curve is called an oblique strophoid. If, in addition, OA is perpendicular to C then the curve is called a right strophoid, or simply strophoid by some authors. The right strophoid is also called the logocyclic curve or foliate.

Contents |

Equations

Polar coordinates

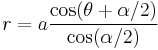

Let the curve C be given by  , where the origin is taken to be O. Let A be the point (a, b). If

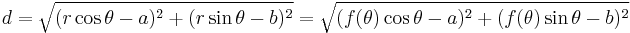

, where the origin is taken to be O. Let A be the point (a, b). If  is a point on the curve the distance from K to A is

is a point on the curve the distance from K to A is

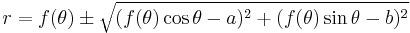

.

.

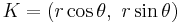

The points on the line OK have polar angle  , and the points at distance d from K on this line are distance

, and the points at distance d from K on this line are distance  from the origin. Therefore the equation of the strophoid is given by

from the origin. Therefore the equation of the strophoid is given by

Cartesian coordinates

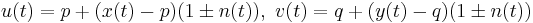

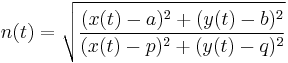

Let C be given parametrically by (x(t), y(t)). Let A be the point (a, b) and let O be the point (p, q). Then, by a straightforward application of the polar formula, the strophoid is given parametrically by:

,

,

where

.

.

An alternative polar formula

The complex nature of the formulas given above limits their usefulness in specific cases. There is an alternative form which is sometimes simpler to apply. This is particularly useful when C is a sectrix of Maclaurin with poles O and A.

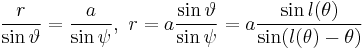

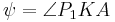

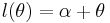

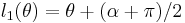

Let O be the origin and A be the point (a, 0). Let K be a point on the curve,  the angle between OK and the x-axis, and

the angle between OK and the x-axis, and  the angle between AK and the x-axis. Suppose

the angle between AK and the x-axis. Suppose  can be given as a function

can be given as a function  , say

, say  . Let

. Let  be the angle at K so

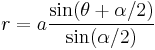

be the angle at K so  . We can determine r in terms of l using the law of sines. Since

. We can determine r in terms of l using the law of sines. Since

.

.

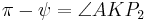

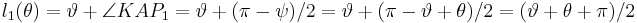

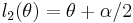

Let P1 and P2 be the points on OK that are distance AK from K, numbering so that  and

and  .

.  is isosceles with vertex angle

is isosceles with vertex angle  , so the remaining angles,

, so the remaining angles,  and

and  , are

, are  . The angle between AP1 and the x-axis is then

. The angle between AP1 and the x-axis is then

.

.

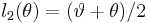

By a similar argument, or simply using the fact that AP1 and AP2 are at right angles, the angle between AP2 and the x-axis is then

.

.

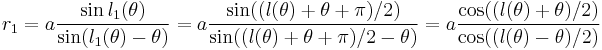

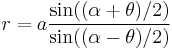

The polar equation for the strophoid can now be derived from l1 and l2 from the formula above:

C is a sectrix of Maclaurin with poles O and A when l is of the form  , in that case l1 and l2 will have the same form so the strophoid is either another sectrix of Maclaurin or a pair of such curves. In this case there is also a simple polar equation for the polar equation if the origin is shifted to the right by a.

, in that case l1 and l2 will have the same form so the strophoid is either another sectrix of Maclaurin or a pair of such curves. In this case there is also a simple polar equation for the polar equation if the origin is shifted to the right by a.

Specific cases

Oblique strophoids

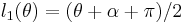

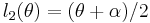

Let C be a line through A. Then, in the notation used above,  where

where  is a constant. Then

is a constant. Then  and

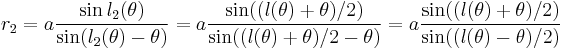

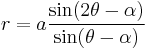

and  . The polar equations of the resulting strophoid, called an oblique strphoid, with the origin at O are then

. The polar equations of the resulting strophoid, called an oblique strphoid, with the origin at O are then

and

.

.

It's easy to check that these equations describe the same curve.

Moving the origin to A (again, see Sectrix of Maclaurin) and replacing −a with a produces

,

,

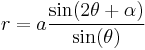

and rotating by  in turn produces

in turn produces

.

.

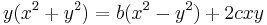

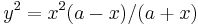

In rectangular coordinates, with a change of constant parameters, this is

.

.

This is a cubic curve and, by the expression in polar coordinates it is rational. It has a crunode at (0, 0) and the line y=b is an asymptote.

The right strophoid

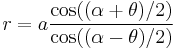

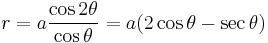

Putting  in

in

gives

.

.

This is called the right strophoid and corresponds to the case where C is the y-axis, O is the origin, and A is the point (a,0).

The Cartesian equation is

.

.

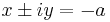

The curve resembles the Folium of Descartes and the line x = −a is an asymptote to two branches. The curve has two more asymptotes, in the plane with complex coordinates, given by

.

.

Circles

Let C be a circle through O and A, where O is the origin and A is the point (a, 0). Then, in the notation used above,  where

where  is a constant. Then

is a constant. Then  and

and  . The polar equations of the resulting strophoid, called an oblique strphoid, with the origin at O are then

. The polar equations of the resulting strophoid, called an oblique strphoid, with the origin at O are then

and

.

.

These are the equations of the two circles which also pass through O and A and form angles of  with C at these points.

with C at these points.

References

- J. Dennis Lawrence (1972). A catalog of special plane curves. Dover Publications. pp. 51–53,95,100–104,175. ISBN 0-486-60288-5.

- E. H. Lockwood (1961). "Strophoids". A Book of Curves. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–137. ISBN 0521055857.

- R. C. Yates (1952). "Strophoids". A Handbook on Curves and Their Properties. Ann Arbor, MI: J. W. Edwards. pp. 217–220.

- "Courbe Strophoïdale" at Encyclopédie des Formes Mathématiques Remarquables (in French)

- "Strophoïde" at Encyclopédie des Formes Mathématiques Remarquables (in French)

- "Strophoïde Droite" at Encyclopédie des Formes Mathématiques Remarquables (in French)

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Strophoid" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Right Strophoid" from MathWorld.

- Sokolov, D.D. (2001), "Strophoid", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=S/s090630

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Right Strophoid", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Curves/Right.html.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.